From tree to bowl

This page is an introduction to the art of woodturning and a window to the world of trees and the ecosystem that surrounds our workshop, on mount Kaimaktsalan. Navigate with the help of the side buttons.

Read through the chapters to follow the steps of the process.

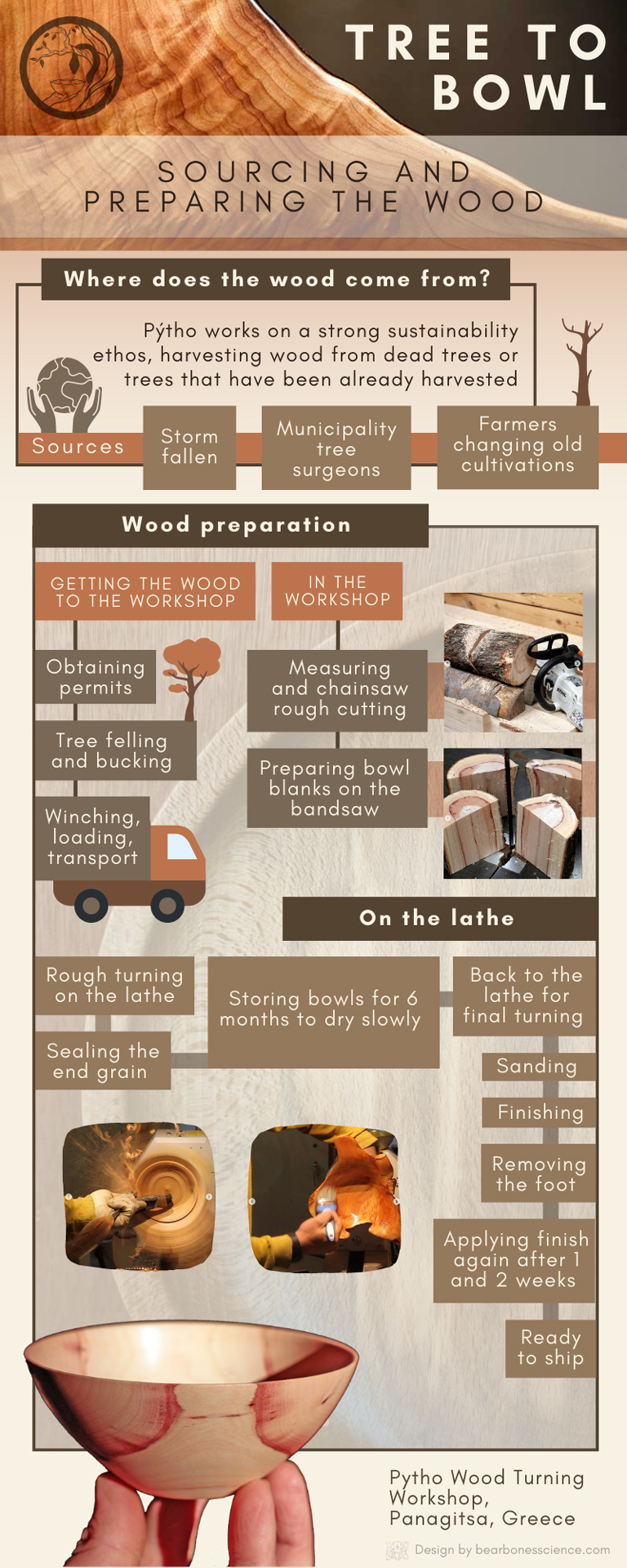

Have a look at a nice infographic that offers a helpful perspective.

At any point you can refer to the glossary, hover over the cards with your cursor to see a picture example.

This page would be incomplete without a reference of tree species we use, each with its own unique character. Click here to jump to a section about bowl care.

Sources of timber

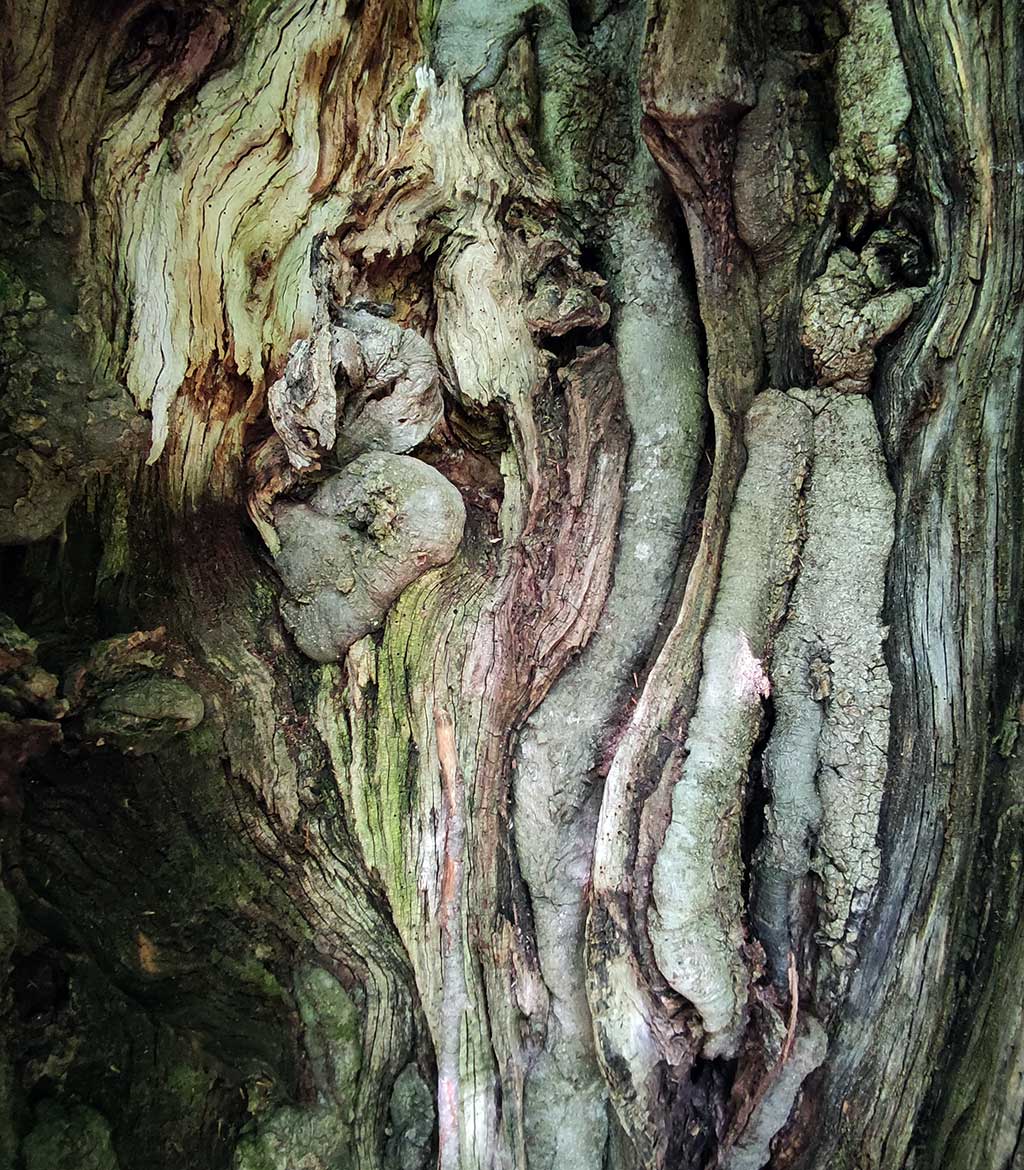

Unlike luthiers or cabinet makers wood turners appreciate timber with imperfections. The more adventurous the life of a tree has been the more stories it contains in its grain patterns. Thus we can work with the waste of the forest: fallen, decaying, twisted, knotted trees are our heart’s delight.

We are in contact with foresters, municipality tree surgeons and farmers and through them we have a steady supply of timber without ever cutting a living tree. I have to admit, fallen trees are not a sad sight for me anymore, I shamelessly see bowls and platters after a big storm.

Sometimes located deep in the forest, carrying a fallen tree to the workshop is a challenge. A permit is required and then time spent inspecting the tree to visualise then and there possible forms and vessels it can give us, before any cuts. Then we have to winch it, lift it and carry it to the workshop.

Trees are a majestic part of an ecosystem. Four giants I meet in the forest, an ancient oak, is home to countless organisms, from fungi to small mammals. A dead chestnut hides an ant colony, a lightning struck plane tree is home to a colony of bats and a black pine always nests birds of pray. It goes without saying that after human laws we also need to have a code of ethics about what we remove from the forest and never disturb the balance.

Wood preparation

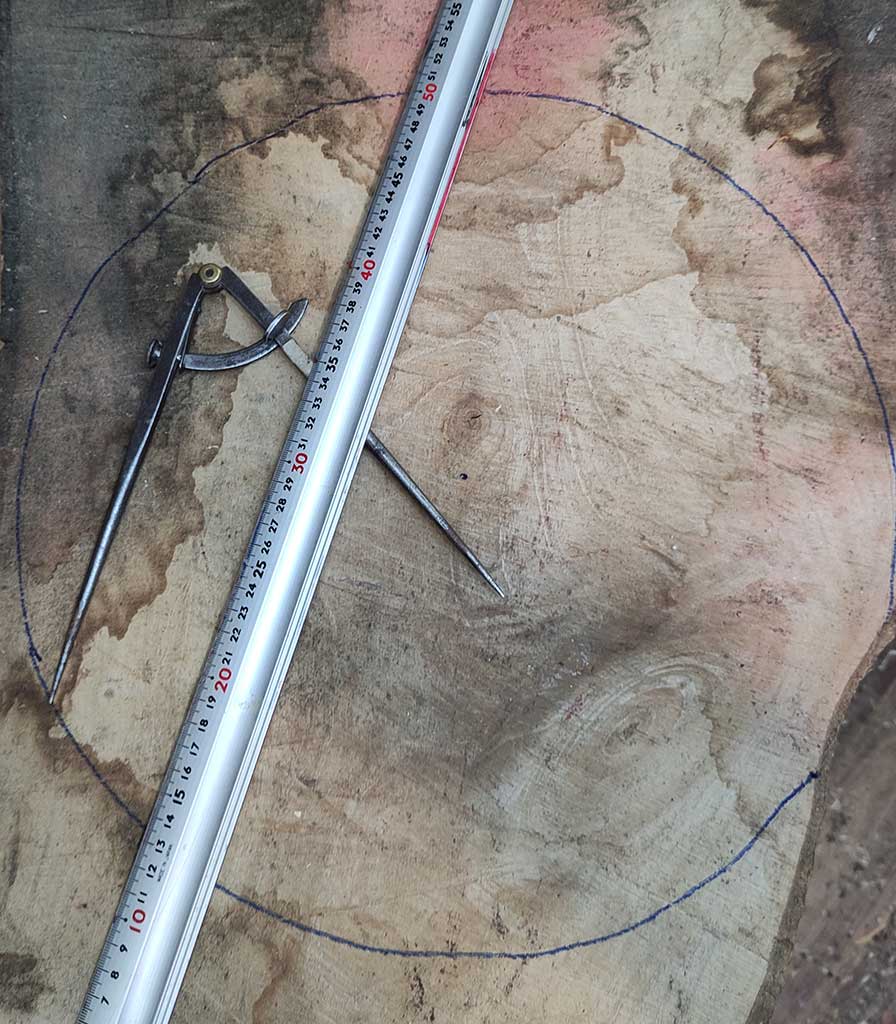

Once at the workshop, logs are measured, marked and cut with a chainsaw to a rough shape, have a look at the slices on the slideshow next to this text. The direction of cut will determine the strength and behaviour of the wood and the durability of the vessel.

Every part of the tree has it’s own characteristics. Different qualities are present near the root, in the main trunk, where branches start and so on. Moreover the trunk is further divided in four parts, from inside out these are the central part also called pith, the heartwood (harder wood that is no longer alive), the sapwood (softer wood with living cells that transfer nutrients and water) and the bark. All these are utilised and each behaves distinctly!

Next we move to the bandsaw where so called “bowl blanks” are shaped, as close as possible to a circular shape. Finally we can start work on the lathe.

On the lathe

As you’ve provably realised making a wooden bowl is a long process, we are halfway there now. The wood spins on the lathe and with sharp hand tools we give it a rough shape, making an ultra-thick bowl.

Depending on the tree species this bowl needs four to six months to dry before we give it its final shape. We apply a sealant to block the pores of the wood and store it – we want the wood to dry as slow as possible to avoid cracking. In storage it will change shape, flex and bend. When it returns to the lathe it will be turned again and then move on to the last stage – sanding and finishing.

This is one method, also called “twice turning”, it gives us perfectly circular bowls of any thickness we like. There is another method called Green Turning. You could be taking a walk in the forest in the morning, pick up a fallen branch and eat a salad in a bowl made from it for dinner. In green turning we use fresh wood, turn it immediately into a (very) thin-walled bowl that dries after it’s created. As it dries it will twist and turn until it takes a unique shape. We know how to predict it but still surprises are more common than not. It is a fast process but requires good technique and knowledge of the wood. Of course there is no uniformity but that’s what we love about it!

Finishing

The last step of the process has two stages, sanding and oiling. The grain of the wood is finally revealed and then suddenly the wood becomes alive when finishing oil is applied. It is a long and strenuous process – all done in a cloud of dust.

Just before finishing we make a finishing cut, a very delicate pass with a sharp tool to clean any tool marks. Then the vessel is sanded starting from low grit sandpaper progressively moving to finer grits until we have the result we want – not every object has to be glass – polished!

Recipes and application techniques of finishing oils and varnishes tend to be a trade secret for woodworkers. In our workshop we use edible flaxseed oil and for some applications beeswax and orange essential oil as well, and that’s it.

Bowl care

- Our bowls are finished with natural, food safe oils, mainly edible flaxseed oil.

- After use wash with lukewarm water and if necessary a mild detergent, dry right away with a kitchen towel

- Do not soak in water or leave in the sink.

- Wooden vessels are not dishwasher / microwave safe.

- Avoid storing in direct sunlight or close to a heat source.

- Periodically apply flaxseed oil or food grade mineral oil to protect the wood and enliven its colours.

- Bowls, plates and platters are safe to use with any food – beets and turmeric might transfer colour to the wood!

- Lidded boxes are suitable for dry storage (tea, coffee, herbs, salt, sugar, rice, beans and so on).

- Live edge vessels are somewhat sensitive as the bark at the rim can chip off if nicked. They can still be used for salads, popcorn or as fruit bowls.

- Spalted vessels are best used as decorative elements or to hold nuts and fruits, not suitable for liquids or warm food.

- Our thin cups can slightly change shape momentarily or permanently when they hold hot liquids – this is a normal and expected behaviour. Ultra-thin cups are best for cold liquids as hot tea or coffee can filter through their walls! We still use them like that, just a warning 🙂

- Lamps are best fitted with LED lights that produce low heat levels.

Glossary

Grain

Spalting

Green Wood

The Trunk

Growth Rings

Burl

Parts of a Tree

Tree Crotch

Bowl Blank

Yunomi - Obon

Nested Bowls

Open Form

Spindle

Closed Form

Live Edge

Hollow Form

Woodturning

Coring

Lathe

Face Turning

Chuck

Spindle Turning

Tools

Sharpening

Grain

Spalting

Green Wood

The Trunk

Growth Rings

Burl

Parts of a Tree

Tree Crotch

Bowl Blank

Yunomi - Obon

Nested Bowls

Open Form

Spindle

Closed Form

Live Edge

Hollow Form

Woodturning

Coring

Lathe

Face Turning

Chuck

Spindle Turning

Tools

Sharpening

Tree species reference

(under construction)

E

Elm

Eucalyptus

F

G

H

Hazel

Hornbeam

Hawthorn

I

J

Juniperus

K

L

M

Mulberry

Maple

N

O

Oak

Olive

P

Plane

Poplar

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

Walnut

Wild Pear

Willow

Wild Cherry

X

Y

Z

Alder (Alnus glutinosa) is a fast growing, short-lived tree that thrives in wet locations and grows to a height of up to 30 metres. It provides food and shelter for wildlife and it is a very important tree for the forest ecosystem.

Uses: The wood is white when first cut, turning to pale red as it dries. It is very durable under water (Venice is supported on alder beams) and is a wonderful soft wood for turnery, carving, furniture making, window frames and toys. It is an excellent tonewood used in electric guitars and other instruments. The bark and other parts of the tree are used in dyeing producing yellow, green, pink and black dyes. It has too many medicinal uses to mention here but you can find them on the linked article. It supplies high quality charcoal and is used to produce smoked foods.

Turning: we love using alder to make breakfast bowls and plates as well as larger boxes, toys and educational material. Older trees often get uprooted in stormy weather but despite any abundance of timber you won’t find alder vessels in shops. Upsides: colour, grain, easily absorbs finishes, not affected by water. Downsides: softer wood will be dented by sharp objects.

Beech (Fagus) is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to temperate Europe, Asia, and North America. Recent classifications recognize 10 to 13 species in two distinct subgenera, Engleriana and Fagus. The Engleriana subgenus is found only in East Asia, distinctive for its low branches, often made up of several major trunks with yellowish bark. The better known Fagus subgenus beeches are high-branching with tall, stout trunks and smooth silver-grey bark. The European beech (Fagus sylvatica) is the most commonly .