My apprenticeship started under my father, in the form of play and with a narrative of exploration and adventure. We always lived close to nature, our first home was on a tiny island called Tilos, then we moved to the mountains of Northern Greece. These rich ecosystems provided countless stimuli, from a microscopic to a grand level, shapes, scents, colours.

My apprenticeship started under my father, in the form of play and with a narrative of exploration and adventure. We always lived close to nature, our first home was on a tiny island called Tilos, then we moved to the mountains of Northern Greece. These rich ecosystems provided countless stimuli, from a microscopic to a grand level, shapes, scents, colours.

Wherever we were, a workshop was soon set up. We were making beehives, musical instruments, toys, weaving baskets or building furniture. I learned but also witnessed my father learning. The now lost art of weaving sturdy baskets from olive tree shoots he learned from an old man and his sister. They lived at a cliff by the sea with no connection to the civilised world. The old man was giving his secrets in small portions and his sister was telling stories of sea creatures. He never taught him how to tie the end of a basket, ensuring their relationship wouldn’t end.

My first study was in music. A similar form of apprenticeship, face to face, ear to ear. Hands and mind busy creating sound but in reality, in the mind of the musician, sound is also shapes, colours, flavours, forms and faces, invisible but very much there.

This way of learning was fun, unlike formal education. Right after finishing school, appalled by what we went through, my sisters and I put it in words “what if the way we grew up could become inspiration for a different kind of education?”. We all embarked in studies that allowed us to explore this idea.

When these cycles of learning completed we returned to the mountain and started our experimental practical school in 2013, of course a woodworking studio became part of it soon.

I spent some years locked in the workshop, further training my hands in tool work and my mind in shapes and symmetries. Now there is Pytho, a woodturning studio and Children’s Orchard, our little school for the children of the mountain.

I work with already dead trees that often have had adventurous lives, they are more inspiring I find. Pýthō means decaying and it’s a word with rich history, read on if you are into the secret lives of words.

Pýthō is an ancient greek word meaning “to decay, to rot”. It originates from the older Sanskrit word pūyati of the same meaning. The root *pu- is perhaps an even older, pre-language, echoic “word” a natural exclamation of disgust.

The first name of the ancient city of Delphiwas Pýthō, the most important oracle site of Greece. The city was named after Python, son of goddess Gaia, the ancestral mother of all life. He was an enormous dragon-serpent which was produced from the mud after the flood of Deucalion. He served as the original keeper of the oracle at Delphi and lived in a cave on Mount Parnassus

.

“When the Earth, deep-coated with the slime of the late deluge, glowed again beneath the warm caresses of the shining sun, she brought forth countless species, some restored in ancient forms, some fashioned weird and new. Indeed Earth against her will produced a Serpent never known before, the huge Python, a terror to men’s new-made tribes, so far it sprawled across the mountainside. The Archer god Apollo, whose shafts till then were used only against she-goats and fleeing does, destroyed the monster with a thousand arrows, his quiver almost emptied, and the wounds, black wounds, poured forth their poison. (Ovid’s Metamorphoses, A. D. Melville and Edward J. Kenney)

Hidden in this story there is a very visual and simple allegory: early every morning, the dispersal of the fogs and clouds of vapour that arise from ponds and marshes (Python) by the rays of the sun (the arrows of Apollo, the sun-God). (Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). “Python, in Greek mythology”)

A cycle between darkness and light, decay and birth. This is a painting by J. M. W. Turner, Apollo and Python. He was aware of the symbolism, the victory of sun and light over mist and darkness.

Mt. Voras (2524m / 8281 ft) is named after the mythical Voreas, son of Aeolus, ruler of the winds. Voreas was the personification of winter storms, common on the mountain, and wild horses. Another name of the mountain is Kaimaktsalan, the turkish word for buttercream because of its snowy peaks.

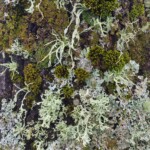

The mountain range is a Natura 2000 protected area with large forests of beech, pine, oak, chestnut, juniper, hornbeam, hazel, birch and other species of trees. On its alpine slopes there are hundreds of plant species including Ranunculus cacuminis, endemic only to the peak of this mountain, the impressive Geum coccineum and lilium martagon . Alder and plane groves grow alongside its rivers and streams.

Rocky peaks, dense forests, alpine meadows and isolation (the mountain is the natural border of Northern Greece with no roads or border crossings to the north from here) provide a biotope for wild animals and birds. Vultures, eagles, buzzards, horned owls, woodpeckers and a hundred other species of birds can be observed. Hares, squirrels, hedgehogs, European otters, badgers and pine martens are some of the small mammals that thrive while there are recovering numbers of bears, wolves, jackals, deer, wild boar and wild cats.

On account of its geographical location the mountain has a dense history of battles and struggles that have left their mark both to the mountain and its people. We regularly organise guided tours for the exploration of the flora and fauna and the local history through our social cooperative. More information about this ecosystem and opportunities to explore it can be found on www.bearbonesscience.com, Dr Angeliki’s Savvantoglou website about her research on the mountain.

If you visit for woodturning lessons there are many points of interest to explore within a 20km radius of our workshop.

- A ski centre

- A hike to the top of the mountain, the church of Profitis Elias

- The Black Forest

- Lake Vegoritida

, lake Petron

and lake of Agras

- Numerous pristine rarely visited hike paths

- The city of Edessa with its waterfalls

- The hot springs of Pozar and the river gorge trek of Moglenitsa

- The traditional village of Nymfeon, home to a bear sanctuary

- Many sites of importance to local history like the abandoned village of Ksanthogeia or the partisan’s hideouts on the slopes of Voras

Toggle Content

My apprenticeship started under my father, in the form of play and with a narrative of exploration and adventure. We always lived close to nature, our first home was on a tiny island called Tilos, then we moved to the mountains of Northern Greece. These rich ecosystems provided countless stimuli, from a microscopic to a grand level, shapes, scents, colours.

My apprenticeship started under my father, in the form of play and with a narrative of exploration and adventure. We always lived close to nature, our first home was on a tiny island called Tilos, then we moved to the mountains of Northern Greece. These rich ecosystems provided countless stimuli, from a microscopic to a grand level, shapes, scents, colours.

Wherever we were, a workshop was soon set up. We were making beehives, musical instruments, toys, weaving baskets or building furniture. I learned but also witnessed my father learning. The now lost art of weaving sturdy baskets from olive tree shoots he learned from an old man and his sister. They lived at a cliff by the sea with no connection to the civilised world. The old man was giving his secrets in small portions and his sister was telling stories of sea creatures. He never taught him how to tie the end of a basket, ensuring their relationship wouldn’t end.

My first study was in music. A similar form of apprenticeship, face to face, ear to ear. Hands and mind busy creating sound but in reality, in the mind of the musician, sound is also shapes, colours, flavours, forms and faces, invisible but very much there.

This way of learning was fun, unlike formal education. Right after finishing school, appalled by what we went through, my sisters and I put it in words “what if the way we grew up could become inspiration for a different kind of education?”. We all embarked in studies that allowed us to explore this idea.

When these cycles of learning completed we returned to the mountain and started our experimental practical school in 2013, of course a woodworking studio became part of it soon.

I spent some years locked in the workshop, further training my hands in tool work and my mind in shapes and symmetries. Now there is Pytho, a woodturning studio and Children’s Orchard, our little school for the children of the mountain.

I work with already dead trees that often have had adventurous lives, they are more inspiring I find. Pýthō means decaying and it’s a word with rich history, read on if you are into the secret lives of words.

Pýthō is an ancient greek word meaning “to decay, to rot”. It originates from the older Sanskrit word pūyati of the same meaning. The root *pu- is perhaps an even older, pre-language, echoic “word” a natural exclamation of disgust.

The first name of the ancient city of Delphiwas Pýthō, the most important oracle site of Greece. The city was named after Python, son of goddess Gaia, the ancestral mother of all life. He was an enormous dragon-serpent which was produced from the mud after the flood of Deucalion. He served as the original keeper of the oracle at Delphi and lived in a cave on Mount Parnassus

.

“When the Earth, deep-coated with the slime of the late deluge, glowed again beneath the warm caresses of the shining sun, she brought forth countless species, some restored in ancient forms, some fashioned weird and new. Indeed Earth against her will produced a Serpent never known before, the huge Python, a terror to men’s new-made tribes, so far it sprawled across the mountainside. The Archer god Apollo, whose shafts till then were used only against she-goats and fleeing does, destroyed the monster with a thousand arrows, his quiver almost emptied, and the wounds, black wounds, poured forth their poison. (Ovid’s Metamorphoses, A. D. Melville and Edward J. Kenney)

Hidden in this story there is a very visual and simple allegory: early every morning, the dispersal of the fogs and clouds of vapour that arise from ponds and marshes (Python) by the rays of the sun (the arrows of Apollo, the sun-God). (Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). “Python, in Greek mythology”)

A cycle between darkness and light, decay and birth. This is a painting by J. M. W. Turner, Apollo and Python. He was aware of the symbolism, the victory of sun and light over mist and darkness.

Mt. Voras (2524m / 8281 ft) is named after the mythical Voreas, son of Aeolus, ruler of the winds. Voreas was the personification of winter storms, common on the mountain, and wild horses. Another name of the mountain is Kaimaktsalan, the turkish word for buttercream because of its snowy peaks.

The mountain range is a Natura 2000 protected area with large forests of beech, pine, oak, chestnut, juniper, hornbeam, hazel, birch and other species of trees. On its alpine slopes there are hundreds of plant species including Ranunculus cacuminis, endemic only to the peak of this mountain, the impressive Geum coccineum and lilium martagon . Alder and plane groves grow alongside its rivers and streams.

Rocky peaks, dense forests, alpine meadows and isolation (the mountain is the natural border of Northern Greece with no roads or border crossings to the north from here) provide a biotope for wild animals and birds. Vultures, eagles, buzzards, horned owls, woodpeckers and a hundred other species of birds can be observed. Hares, squirrels, hedgehogs, European otters, badgers and pine martens are some of the small mammals that thrive while there are recovering numbers of bears, wolves, jackals, deer, wild boar and wild cats.

On account of its geographical location the mountain has a dense history of battles and struggles that have left their mark both to the mountain and its people. We regularly organise guided tours for the exploration of the flora and fauna and the local history through our social cooperative. More information about this ecosystem and opportunities to explore it can be found on www.bearbonesscience.com, Dr Angeliki’s Savvantoglou website about her research on the mountain.

If you visit for woodturning lessons there are many points of interest to explore within a 20km radius of our workshop.

- A ski centre

- A hike to the top of the mountain, the church of Profitis Elias

- The Black Forest

- Lake Vegoritida

, lake Petron

and lake of Agras

- Numerous pristine rarely visited hike paths

- The city of Edessa with its waterfalls

- The hot strings of Pozar and the river gorge trek of Moglenitsa

- The traditional village of Nymfeon, home to a bear sanctuary

- Many sites of importance to local history like the abandoned village of Ksanthogeia or the partisan’s hideouts on the slopes of Voras